OMP’s software crafts scenarios beyond human imagination: Interview with De Tijd

November 29, 2023

Translated interview from De Tijd (in Dutch)

Few Belgian IT companies are as unknown as Belgian-based OMP. And yet its software for the optimal planning of supply, production, and logistics runs in the background at the largest companies in the world. “We got a foot in the door at BASF in Antwerp, Procter & Gamble in Mechelen, Johnson & Johnson in Beerse, and Aperam in Genk. Now we’re in all their branches worldwide.”

What type of beets can the Tienen Sugar Refinery most efficiently send to which factory to make what type of sugar product? It was an issue that Anita Van Looveren, a commercial engineer specializing in quantitative economics, was happy to run a battery of mathematical models on in 1985.

It became one of the first assignments for OMP, an academic spin-off founded by Professor Georges Schepens a year earlier in a villa in Brasschaat, Belgium. At that point, Van Looveren had already been bitten by the math bug and a desire to optimize industrial processes. She became OMP’s first consultant. The company has been nominated for Onderneming van het Jaar (Entrepreneur of the Year) 2023.

It became one of the first assignments for OMP, an academic spin-off founded by Professor Georges Schepens a year earlier in a villa in Brasschaat, Belgium. At that point, Van Looveren had already been bitten by the math bug and a desire to optimize industrial processes. She became OMP’s first consultant. The company has been nominated for Onderneming van het Jaar (Entrepreneur of the Year) 2023.

Meanwhile, OMP traded the villas – which had multiplied from one to four in the same street – for a modern office building in Wommelgem, Belgium, and Van Looveren has been OMP’s CEO for nearly 30 years. The company has become a pioneer and global player in software solutions that helps large industrial companies optimize their production and supply chain planning.

And yet, few people know of the software and consulting company, but that’s completely different within the manufacturing industry: its customer portfolio includes big names like ArcelorMittal, BASF, Bayer, Bekaert, Johnson & Johnson, Nestlé, Procter & Gamble, and Roche. Sales have doubled over the past four years, now totaling 200 million euros. It employs 1,100 people, with around 600 in Belgium and the rest in the 9 other locations around the world.

What makes OMP’s planning software, called Unison Planning™, so beloved by those multinational giants? This is where the story of sugar production helps.

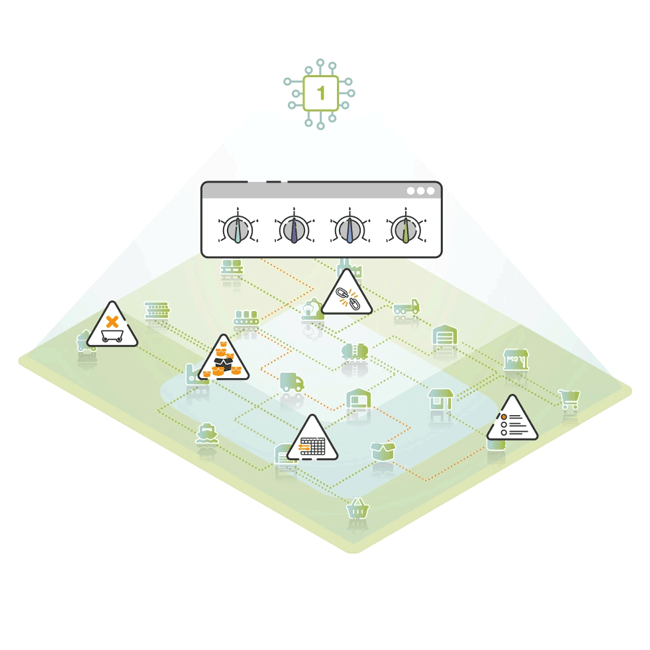

“In that case, you had a few hundred possible outcomes based on a limited amount of variables in the production of Tienen Sugar,” Van Looveren explains. “In principle, Excel tables still work perfectly well for that. But if you have to make this kind of planning for large companies with thousands of parameters, and not only in production, but also in all the steps before and after (supply of raw materials, the purchase of energy, the storage of semi-finished products, and distribution and logistics to the customer) then you come to millions of possible combinations, which a human being can never oversee, let alone interpret. Our software, plus increasingly more AI, ensures that out of all those possibilities, the most efficient planning is chosen.”

"If you handle supply chain planning for large companies with thousands of parameters, you face millions of possible combinations, which a human being can never oversee, let alone interpret.”

In doing so, OMP only focuses on about six industries: chemicals, life sciences, consumer goods, metals, paper, film & packaging, and building products. “We have the top three companies as customers in every sector in which we operate,” says Van Looveren. “We provide those customers not only with software, through a platform running in the cloud, but also with consulting and services, such as training.”

A broadened scope

Paul Vanvuchelen, once Chief Performance Officer at stainless steel producer Aperam, still monitors that industry and others at OMP as Director of Customer Solutions. “Not only do we offer the software at each step of the chain, but also at three different levels.”

Paul Vanvuchelen, once Chief Performance Officer at stainless steel producer Aperam, still monitors that industry and others at OMP as Director of Customer Solutions. “Not only do we offer the software at each step of the chain, but also at three different levels.”

“The first layer is operational: what production volumes are expected based on the number of orders coming in, how many alloys and scraps need to be delivered for that day and week, how do we need to reinforce the shifts, how do you keep the number of costly machine changeovers as low as possible, how do you avoid waste, how many steel coils need to go into the warehouses after production and how many need to be transported to the distributor immediately, and so on. This is where our software runs every day or even around the clock (24/7), based on increasingly new input, such as disruptions in certain production lines or newly received orders, for example.”

“Then, in the tactical layer, the software predicts – over a period of three to eighteen months – how big the budget needs to be, and consequently how the machinery has to be expanded or reduced, whether three, four, or five shifts will work and in which factories, what the margins are going to be at a given raw material and energy price, how to then conduct your contract negotiations, and so on.”

“The third, strategic layer drives decisions such as the construction of new production lines and/or factories or the choices of market for the steel. Actually, our software is a very large simulator that constantly gives you work to do. Plus, the inclusion of ecological parameters, such as the carbon footprint, becomes more important as companies must increasingly report on their sustainability.”

“The third, strategic layer drives decisions such as the construction of new production lines and/or factories or the choices of market for the steel. Actually, our software is a very large simulator that constantly gives you work to do. Plus, the inclusion of ecological parameters, such as the carbon footprint, becomes more important as companies must increasingly report on their sustainability.”

Over the years, not only has the scope – the three layers and the entire chain from raw material to end customer – expanded, but also how deeply the software has penetrated its customers. “With a BASF, for example, we came in through their facility in the Port of Antwerp,” says Kurt Gillis, Director of Business Development. “But today, our system is running throughout the whole of the German chemical group. We got a foot in the door at Procter & Gamble in Mechelen, Johnson & Johnson in Beerse, and Aperam in Genk, all in Belgium. Now we’re in all their branches.” Thanks to these references, we’re also able to get straight into the full group from the start. In the next three years, for example, we’ll be rolling out our software platform in all three hundred Nestlé factories.

Increasingly more artificial intelligence and machine learning are being implemented on top of the mountain of data that feeds the Unison Planning software. “That way, you can depart from the traditional trend analysis, where you carried forward certain conclusions from the past into the future.”

"We can now also use external data, such as macroeconomic indicators, trending topics on social media, or the weather forecast, as input to estimate sales and anticipated production volumes".

Will global food, pharma, or steel groups soon be controlled from computer servers whereby algorithms make the decisions? “There are already so-called smart autonomous systems at the operational level: they can work independently, even solving minor disruptions in production or logistics according to predefined rules,” says Van Looveren. “But human interaction will remain. The latter must make the final choice between several scenarios proposed by the software. But sometimes, it actually does produce scenarios that humans never would have thought of.”

Will global food, pharma, or steel groups soon be controlled from computer servers whereby algorithms make the decisions? “There are already so-called smart autonomous systems at the operational level: they can work independently, even solving minor disruptions in production or logistics according to predefined rules,” says Van Looveren. “But human interaction will remain. The latter must make the final choice between several scenarios proposed by the software. But sometimes, it actually does produce scenarios that humans never would have thought of.”

"The automation of planning allows people to focus more on the strategic aspects.”

Growing along with customers

What do companies get out of Unison Planning? Vanvuchelen’s got the answer. “It can prevent production lines from shutting down for lack of work stocks, store shelves from being empty for too long, COVID-19 vaccines from not getting to citizens on time, e-commerce companies from running low on inventory on Black Friday, and so on. We are also always on the right side. When demand for our customers’ products is low, we help cut costs. When demand is high, we help boost production volumes.”

"If a big pharma company can get its predictions on its demand 5 percent more accurate, that could save the company millions.”

According to research firm Gartner, OMP has a limited number of competitors, the most important of which are Kinaxis, o9, and Blue Yonder. “But there isn’t a player that is so broadly integrated across the supply chain,” Van Looveren argues. “Moreover, we notice a high level of satisfaction among our customers concerning the fact that our consultants have deep knowledge of their industry, and therefore more easily convert things to the software.”

According to research firm Gartner, OMP has a limited number of competitors, the most important of which are Kinaxis, o9, and Blue Yonder. “But there isn’t a player that is so broadly integrated across the supply chain,” Van Looveren argues. “Moreover, we notice a high level of satisfaction among our customers concerning the fact that our consultants have deep knowledge of their industry, and therefore more easily convert things to the software.”

Although OMP claims to have already penetrated the global top three in its focus industries, there is still plenty of work to be done. “There are still quite a few large companies that don’t use our software. Plus, there’s still room to grow with our existing customers: some aren’t using our software in every link of their supply chain yet, or not at every decision level either. We can still grow geographically as well.”

That growth, nearly forty years after its founding, is proceeding faster than ever, at an ever-increasing average of 20 percent per year, and with a gross operating profit margin (EBITDA margin) of more than 20. So that should mean that potential buyers must be knocking on OMP’s door regularly to discuss mergers?

“Big private equity funds definitely notice those great figures, yes,” says Van Looveren. “But the shareholders intend to continue under their own steam.” The shareholders comprise more than 10 percent of the 1,100 employees and the listed investment company Ackermans & van Haaren, which took a 20 percent stake in the group in 2020. “OMP’s long-term philosophy is also Ackermans & van Haaren’s vision. A large part of the turnover is not distributed, but goes toward further development of the company. Then you also don’t need additional capital from the stock market or a fund.”

Fact sheet

- Origin: Academic spin-off, founded in 1985 by professor-emeritus Georges Schepens

- CEO: Anita Van Looveren was the first consultant and has been CEO since 1994

- Activity: Supplies software and services to large manufacturing companies to optimize their supply chain, production, and logistics

- Turnover: 200 million euros (2023)

- Gross operating profit margin: more than 20 percent

- Staff: 1,100, including 600 in Belgium

- HQ: Wommelgem, Belgium, with eight other branches located around the globe

- Customers: ArcelorMittal, BASF, Bayer, Bekaert, Johnson & Johnson, Nestlé, Procter & Gamble, Roche, and many others

- Shareholders: Founders, management, and staff (80%) Ackermans & van Haaren (20%)