Why shorter scheduling cycles will become the new normal in consumer goods

Dirk Van Ginderachter - October 20, 2020

An increasing number of consumer goods companies are gradually moving from weekly to daily supply planning cycles. Some have even managed to bring the cycle down to a time span of just one shop floor shift. The chances are that this will become the new normal for supply chain value creation.

The weekly cycle we all know

Historically, the supply of consumer packaged goods (CPG) has always been on a weekly schedule. At the beginning of the cycle, planners create an unconstrained distribution plan, then update the production plan so that the constrained supply plan can then be deployed.

Blog post

This is a pragmatic solution from the manufacturing point of view, giving planners a manageable workload. Disruptions to supply during the rest of the week are ignored or, at best, addressed by manually adapting the bulk plans, the subsequent finished goods schedules and the distribution plans.

The traditional scheme is far from optimal from a demand perspective, however, because it might take more than a week for producers to adjust their plans to respond to sudden changes in demand. We don’t need a COVID-19 crisis to understand why this could be a problem in a highly competitive and promotion-driven market.

Blog post

Averting undesired knock-on effects

Technical and organizational constraints have helped to keep this planning practice alive. For example, adapting production plans based on DC stockouts is a tricky and burdensome move if separate planning systems are used for production and distribution.

The bulk and finished goods production processes are also subject to complex constraints and interdependencies, such as the availability of dedicated tanks and silos, lot sizes, the availability of components and materials, the use of shared resources, phase-in and phase-out dynamics, and campaigning and changeover optimization.

This means that quick-and-dirty changes to finished goods schedules would inevitably lead to undesired knock-on effects in upstream, downstream or parallel processes. Planning and scheduling processes based on a weekly cycle avert such undesired outcomes.

Urged to bring stock value down

Blog post

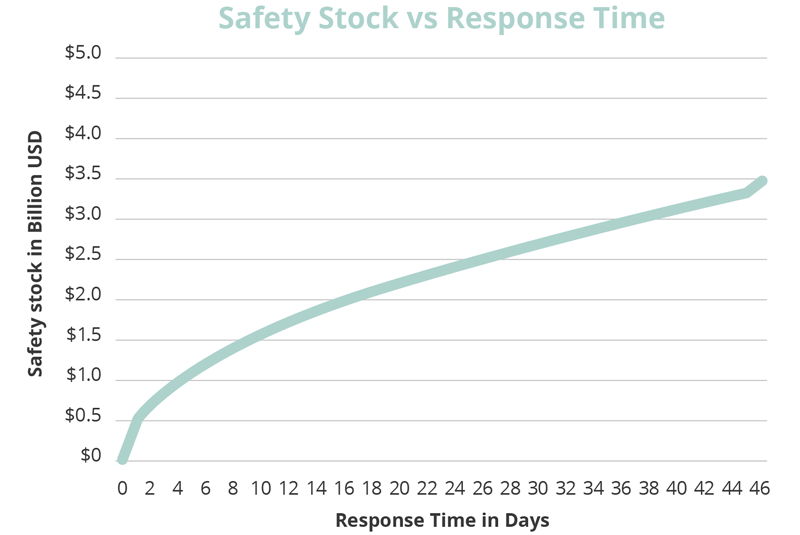

But the markets are forcing the CPG industry to think. Financial considerations require manufacturers to reduce safety stocks and this is closely linked to planning responsiveness. Consider for example a consumer goods company with $50 billion in annual sales volume, a 45% average variation in forecast demand and a 99% target service level.

An operation with a lead time reserved for planning activities of up to 10 days and an additional physical 10-day lead time—would need to keep about $2.3 billion in safety stock (see graph). More agile operational planning based on a daily cycle could bring the value of this stock down to around $1.5 billion, reducing working capital by as much as $0.8 billion.

Blog post

A new normal in the making

There’s no wonder that an increasing number of CPG companies have been reorganizing in recent years to allow for more responsive planning and scheduling processes. They’ve been investing to make their production equipment more flexible and their planning process more integrated and responsive.

At present, most OMP implementation projects in the consumer goods industry are about shortening the planning cycle to just one day or even to a single shift, at least at some plants. I expect this evolution to continue under the pressure of growing market competition and with the help of smarter, faster and better integrated forecasting, planning and scheduling solutions.

It’s a real paradigm shift which comes with a lot of challenges. The organization must adapt, and work processes need to be reengineered. But the CPG leaders of tomorrow are today already clearing these hurdles.

Want to learn more about the trend towards shorter planning cycles in CPG?

Dirk Van Ginderachter

Director at OMP BE

Biography

With 15 years at OMP, Dirk currently works on business development and customer implementation in the life sciences and consumer goods industries, focusing on helping to achieve healthy communities and meeting the needs and aspirations of consumers.